Assistance Animals are no Joke

Assistance Animals are no Joke

Have you heard the one about the landlord who wanted to ban pets in her building? Her tenant thought that one was hilarious! You don’t think that’s funny? You must be a landlord. Because of massive abuse on the part of tenants, on January 28, 2020, HUD issued long-awaited new guidance on a tenant’s right to have an animal as a reasonable accommodation under the Fair Housing Act. We had heard that new guidance was coming. Unfortunately, this guidance tells us a lot that we already knew and doesn’t provide the kind of help to curb abuse that we were looking for. Let’s take a closer look.

The Problem

HUD indicates that 60% of its complaints under the Fair Housing Act involve requests for reasonable accommodations and disability access. Complaints regarding assistance animals are on the rise. HUD acknowledges the need to help landlords distinguish between a person with a non-obvious disability who needs an assistance animal from a person who just wants a pet. Wouldn’t it be great if HUD helped with that?

Assistance Animals

HUD breaks down the two types of “assistance animals”: (1) service animals and (2) support animals (ie. non-service animals that do work, perform tasks, provide assistance, and/or provide therapeutic emotional support for individuals with disabilities). Here’s the key takeaway about assistance animals. They are not pets. They are a medical device just like a CPAP machine or an oxygen tank. While a landlord can ban pets, make pet rules, and can charge a pet fee or pet deposit, a landlord cannot ban an assistance animal, make breed restrictions or other rules, nor can a landlord charge a pet fee or pet deposit. It also goes without saying that a landlord can not charge any fee to merely consider a reasonable accommodation request.

Type I: The Service Animal

A service animal is a dog (or in some cases a small horse, but let’s not talk about that here) that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for the benefit of an individual with a disability (including physical, sensory, psychiatric, intellectual, or other mental disability). Other species of animals, wild or domestic, trained or untrained, are NOT service animals. The work or tasks performed by a service animal must be directly related to an individual’s disability. If there is no work or task performed, the dog should not be considered a service animal (but it still might be classified as a support animal).

Type II: The Support Animal

General rule: even when an animal does not qualify as a service animal, a landlord must make a reasonable accommodation under the Fair Housing Act for animals that are not service animals. A reasonable accommodation is a change, exception, or adjustment to a rule, policy, practice, or service that may be necessary for a person with a disability to have equal opportunity to use and enjoy a dwelling, including public and common use spaces. Keep in mind that it is not necessary for a tenant to submit a written request (it can be oral or written) for a reasonable accommodation nor use any special words to request a reasonable accommodation and it can be made by the tenant or by others on behalf of the tenant.

Reasonable Accommodations

When can a tenant make such a request? This is where HUD really lets us down. Surely when the landlord catches a tenant red-handed with an unpermitted pet in violation of the lease, the landlord doesn’t have to listen to the tenant’s story about how “it’s an assistance animal”. If you think that, you’re wrong. HUD says: “A resident may request a reasonable accommodation either before or after acquiring the assistance animal. An accommodation also may be requested after a housing provider seeks to terminate the resident’s lease or tenancy because of the animal’s presence, although such timing may create an inference against good faith on the part of the person seeking a reasonable accommodation. However, under the FHA, a person with a disability may make a reasonable accommodation request at any time, and the housing provider must consider the reasonable accommodation request even if the resident made the request after bringing the animal into the housing.” This is about federal housing policy and you have it plain as day. HUD refuses to step out in the landlord’s favor one bit on this issue. They will protect 99 idiots who want a dog because they want to protect the one person who is actually disabled. This is a policy decision and the inefficiency falls on the landlord (a concept that is kind of in vogue these days).

In making a determination, a landlord is supposed to first ask if a request for a reasonable accommodation has been made. Once made, the landlord has to determine if the tenant has an “observable disability” or the landlord already has information indicating a disability. Examples of observable disabilities are blindness/low vision, deafness/hard of hearing, mobility limitations, some forms of autism, some neurological impairment like a stroke or Parkinson’s disease, etc. which affect major life activities or bodily functions. If a disability is not observable, the landlord can request information regarding the disability and the disability-related need for the animal.

Disability

The kind of information a landlord can request and which can be the basis for supporting a non-observable disability can include (a) a determination of disability from a governmental authority; (b) the receipt of disability benefits or services (ie. SSDI, Medicare, or SSI for a person under 65, veteran’s benefits, etc.); (c) eligibility for housing assistance or housing vouchers received because of disability; (d) information confirming disability from a “health care professional”. Keep in mind that health care professional is more broad than just a doctor and can include an optometrist, psychologist, psychiatrist, physician’s assistant, nurse practitioner, or nurse. Landlords are not entitled to know a tenant’s full diagnosis. In addition, the failure to qualify for benefits does not mean that an individual does not have a disability for Fair Housing purposes.

HUD points out that the Department of Justice guidance on disability has found that some types of impairments will, in virtually all cases, be found to impose a substantial limitation on a major life activity resulting in a determination of a disability. “Examples include deafness, blindness, intellectual disabilities, partially or completely missing limbs or mobility impairments requiring the use of a wheelchair, autism, cancer, cerebral palsy, diabetes, epilepsy, muscular dystrophy, multiple sclerosis, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, obsessive compulsive disorder, and schizophrenia. This does not mean that other conditions are not disabilities. It simply means that in virtually all cases these conditions will be covered as disabilities.”

In the case of non-observable disabilities, a landlord can ask for additional documentation “in order to conduct an individualized assessment of whether it must provide the accommodation under the Fair Housing Act.”

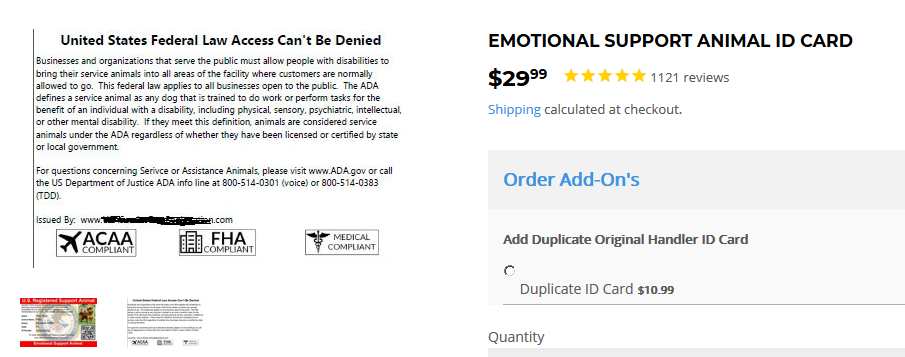

Internet Certifications

The main-event! This is what we’ve all come here for. You all know that a tenant merely needs to google “support animal certification” and for $100 or so, they can have a card that says they have a registered assistance animal? It’s true. Here’s one example of the back of such a card:

This is a card for an EMOTIONAL SUPPORT ANIMAL (not a service animal). Take a look at what the card says: “Businesses and organizations that service the public must allow people with disabilities to bring their service animals into all areas of the facility where customers are normally allowed to go.” That statement is totally true, only it does not apply to support animals. The card has fancy logos that say that the card or maybe the information on it is “ACAA Compliant” and “FHA Compliant” and “Medical Compliant” whatever the heck that means! This is, plain and simple, a scam. For $30, you get a card that is intended to bully and scare a landlord into accepting your pet. What a bargain for the tenant.

Let’s get back to the guidance. Finally, HUD will tell us that those ridiculous internet certifications about animals are bunk and can’t be relied upon, right? Nope. This is why this guidance is trash. HUD addresses the epidemic of internet certifications and says “In HUD’s experience, such documentation from the internet is not, by itself, sufficient to reliably establish that an individual has a non-observable disability or disability-related need for an assistance animal.” That’s a hedge. Then, they go overboard: “By contrast, many legitimate, licensed health care professionals deliver services remotely, including over the internet.” HUD will not throw this baby out with the bath water! So because a legitimate health care professional, what?, uses the internet, we won’t say that these ridiculous cards are invalid? What a waste of everyone’s time.

The guidance goes on to point out that a landlord should make decision on the reasonable accommodation request within 10 days after receipt of documentation from the tenant. They do say that “One reliable form of documentation is a note from a person’s health care professional that confirms a person’s disability and/or need for an animal when the provider has personal knowledge of the individual.” It would have been nice for them to have made this a formal (and the only available) requirement.

Considering the Disability-Related Need

Are you still with me? I’m glad, although I wouldn’t blame someone who bails on this discussion, because we aren’t learning much. So, the landlord has determined that there has been a reasonable accommodation request and there is a disability. Now, the landlord must determine if there is a disability-related need for the assistance animal.

HUD says that reasonably supporting information often consists of information from a licensed health care professional “general to the condition but specific as to the individual with a disability and the assistance or therapeutic emotional support provided by the animal. A relationship or connection between the disability and the need for the assistance animal must be provided.”

Other Animal Types

What about animals that aren’t dogs? If the animal being considered is a dog, cat, small bird, rabbit, hamster, gerbil, other rodent, fish, turtle, or other small, domesticated animal (reptiles other than turtles, barnyard animals, monkeys, kangaroos, etc. are not considered domesticated animals) that is traditionally kept in the home for pleasure rather than for commercial purposes, then the reasonable accommodation should be granted if the landlord has information confirming that there is a disability-related need for the animal.

If the animal is “unique”, like a monkey or a reptile, then the tenant has a burden to demonstrate “a disability-related therapeutic need for the specific animal or the specific type of animal.” There may be reasons that are valid to have a unique animal such as opposable thumbs on a monkey or allergies to dogs. Landlords need to consider special circumstances before approving or denying. Clear as mud, right?

Limitations

HUD doesn’t require a landlord to approve a reasonable accommodation that would constitute a “direct threat to the health or safety of other individuals or whose tenancy would result in substantial physical damage to the property of others.” Landlords can’t impose any rules related to limits on animal breed or size except when specific issues with the animal’s conduct poses a direct threat or a fundamental alteration. So, a landlord can’t say “no pitbulls”. A landlord can ban a specific pitbull with a history of biting people. A tenant is still liable for any damage done by the animal (good luck collecting that).

Denial

A reasonable accommodation request can be denied if it would impose a “fundamental alteration to the nature of the provider’s operations” or if it imposes “an undue financial and administrative burden” on the landlord. If a reasonable accommodation request is denied, the landlord “should engage in the interactive process to discuss whether an alternative accommodation may be effective in meeting the individual’s disability-related needs.”